I’ve built my career in healthcare and tech. I’ve worked with most of the U.S. News top health systems (and some of the worst, according to CMS). I spent several years in strategy at Optum and working closely with UnitedHealthcare.

After 15 years in this industry, not much surprises me anymore. But this still does:

Most providers can tell you, down to the penny, their total patient payments. But ask those same organizations how much they billed to patients? Shockingly, often, they don’t know.

When I sit with revenue cycle leaders, I see systems—and entire teams—that track insurance claims with military precision. Denial rates, accounts receivable (AR) days, payer-specific reimbursement patterns—all measured and monitored in dashboards. Yet those same organizations operate in near-complete darkness when it comes to understanding what they’re asking patients to pay.

Most eventually get to an answer—or at least an acceptable proxy—but it usually takes several weeks and several analysts. Even then, the methodology varies wildly, and the output is often just a “best guess.”

So why the patient billing blind spot?

Personally, I blame the incentives—or lack thereof, even today, with patients typically representing a minor (though fastest-growing) payer in a provider’s book of business.

The patient is indeed at the center of the medical record, but the patient feels like an afterthought in the billing systems built to manage the revenue cycle.

Third party-reimbursement is where the dollars are. It’s what draws the industry’s eyes and attention. Believing that we typically design systems in response to our economic incentives: it’s what electronic health records (EHRs) and “patient” accounting systems were built to optimize—despite the misnomer.

The patient is indeed at the center of the medical record, but the patient feels like an afterthought in the billing systems built to manage the revenue cycle. Only after they’ve been chopped into thousands of diagnosis and procedure codes, packaged up, and shipped off in claims, do teams try to stitch them back to some semblance of a person.

In a very literal sense, the patient is the last bucket in the line, all the way at the end, after the primary, secondary, tertiary, etc. payer buckets. It’s the drain through which the EHR’s pseudo-accounting systems zero out balances. And in systems built to optimize third-party reimbursement and clear AR, the industry has underinvested in the tools necessary to monitor what flows through that drain. Measuring patient billing is tough in systems that were never built for that purpose. The most common approach we see is to “wait until the end,” until an account is closed. After the digital dust has settled, you can approximate what patient responsibility was by “adding up” where the dollars went. The problem? This misses the chaos that happens when we’re actually billing patients.

The source of truth seems kind of…unreliable?

At Cedar, we’re often reminded that the EHR must remain the source of truth. Putting aside my (clearly) biased opinion on whether these systems are fit for that role beyond clinical setting, we’ve held to this at the request of our clients. We’ve built data models that defer to the EHR’s balance as the source of truth on what patients should owe.

However, when I look at what the EHR says patients should owe, I’m frequently left scratching my head. In the flow of balances in and out of the patient bucket, you see the wastewater runoff of processes never designed with human-end users in mind.

A few examples:

- What exactly does the patient owe? Over the last ten years, the revenue cycle has only grown more difficult for providers to manage, and for EHRs to answer that question. As payers have pushed a greater share of costs to consumers via increasing deductibles, they’ve left providers the task of collecting these dollars from patients. Meanwhile, denials have only gotten worse, exposing consumers—now with skin in the game— to a system breaking under pressure. Providers operating on razor-thin margins have (understandably) turned to “free” EHR solutions that can accelerate cash flow, like split billing that allows them to bill patients before insurance fully resolves.

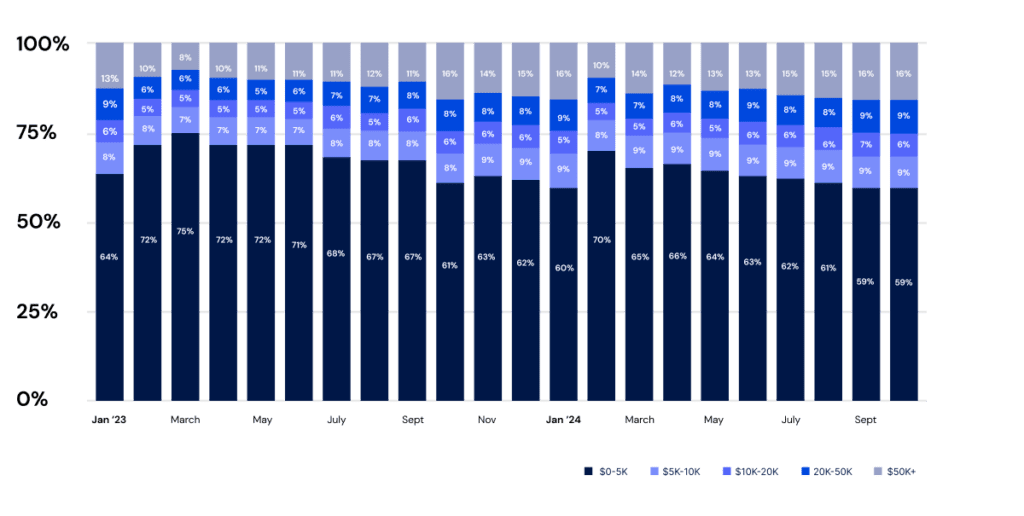

But these approaches can create volatility in patient accounts. Split billing requires intricate orchestration of contract rules and expected reimbursements across payers. When anything goes wrong—e.g., expired coverage, contract mismatches—that house of cards collapses onto the patient. Their account becomes a revolving door of fluctuating balances as adjustments are applied and reversed, bouncing amounts between responsible parties. People expect clarity about what they owe, not bills that change after the fact. Should we be surprised that systems designed for talking to clearinghouses aren’t great at talking to people? - Sorry, how much? When you can finally pin them down, the size of many bills has become unsustainable for patients. Our data shows that patients are increasingly asked to pay balances of $10,000, $20,000, even $50,000 or more.1 When most Americans would struggle to afford an unexpected bill over $1,000, I’ve seen bills in the hundreds of thousands of dollars. Why send these? I understand the “why not” rationale, if only as a last-ditch effort before a certain writeoff. But bills this large seem more likely to net negative headlines than dollars. In an era when public trust in physicians and hospitals is dangerously low, we need to take a serious look at what we’re sending into the community.

Large patient bills ($5,000+) as a growing percentage of total patient responsibility:

Jan 2023 – Oct 2024

- When the only tool you have is a hammer… Shops that track patient billings typically look at a total number and balance after insurance. When we analyze patient “totals” by claim adjustment code, we see they’re actually a mix of different patient responsibility scenarios. Yet every account receives the same, heavy-handed, “send them a bill for this amount” treatment from EHRs, despite vast differences in expected yield and steps required from the patient to resolve. There are more effective ways to engage someone for a Coordination of Benefits denial than chasing them with a (proverbial) hammer, hoping we might scare them into calling with their insurance information via a six-figure bill.

Bottom line

If we can’t see what we’re billing patients, we can’t possibly fix it. And while measuring that is hard work—I’m not saying it’s easy—it’s work worth doing.

Beyond the growing importance of patient collections in the overall financial picture, it’s simply the right thing to do. Looking at our revenue cycle today, can we really say we do no harm?

There’s a seething tension in this country over the cost of care, and providers need to invest in systems that monitor not only clinical outcomes but also the financial well-being of our community. When we send a bill, it impacts real peoples’ lives. It’s at that moment they need clarity, options, and support, and when we should measure patient billings—not months later after the bill “closes.”

That’s why Cedar is investing in deepening our analytics models. Each bill tells a story—from charges and adjustments that explain its genesis to payments, charity care, and bad debt that resolve it. From that understanding, we can develop models that identify optimal pathways for resolution—delivering personalized experiences to help patients address their bills.

It’s a false tradeoff here, between mission and margin. Done right, they actually align. We see a beautifully linear relationship between bill size and expected yield: the larger the bill you send, the less you should expect to collect. But we’ve found it’s possible to bend that statistical truth. Take payment plans, where we’ve demonstrated collections above 90%,2 on balances that would otherwise return pennies on the dollar.33

Connecting patients to the right financial resources starts with understanding what we’re asking them to pay. Until we architect systems to measure, understand, and optimize what patients are actually being billed—and what they can realistically afford—no amount of digital payment features will solve the underlying problem. A system that can’t see that isn’t just flawed—it’s blind and broken. And that’s a bill that in the end, one way or another, we’ll all eventually have to pay.

Spencer Graves is Senior Director, Commercial Strategy at Cedar

- Based on the monthly distribution of patient bill amounts between January 2023 and November 2024 across a sampling of Cedar health system clients. ↩︎

- Based on 2024 PFX Benchmarks for payment plan recovery rate across Cedar health system clients in the 90th percentile. ↩︎

- Based on a comparison between 2024 PFX Benchmarks for median payment plan recovery rate and median post-visit patient collection rate. ↩︎